Madhava raised his hand during the temple board meeting, cutting off Raghunath mid-sentence. “We need to decide this together, as a community. Everyone should have input on how we teach the philosophy class.”

Raghunath’s jaw tightened. He’d been explaining why the teacher needed demonstrated competence in shastra, not popularity. “This isn’t a democracy. Would you let everyone vote on whether gravity exists? Either someone knows the siddhanta or they don’t.”

“That’s so elitist,” Madhava said, shaking his head. “Krishna consciousness is about love, not intellectual gatekeeping. We should honor everyone’s voice.”

“And I’m saying words have meanings. If we’re teaching Bhagavad-gita, we should teach what it actually says, not what feels good to a committee.”

The other board members shifted in their seats. This same argument had erupted three times in as many months. Different surface issues (last time it was festival planning, before that, temple governance) but always the same underlying friction. Madhava wanted consensus, collective experience, the warmth of community deciding together. Raghunath wanted standards, intellectual honesty, respect for those who’d actually studied.

Both men had been devotees for over fifty years. Both were sincere. Both were utterly convinced the other was missing something fundamental about Krishna consciousness.

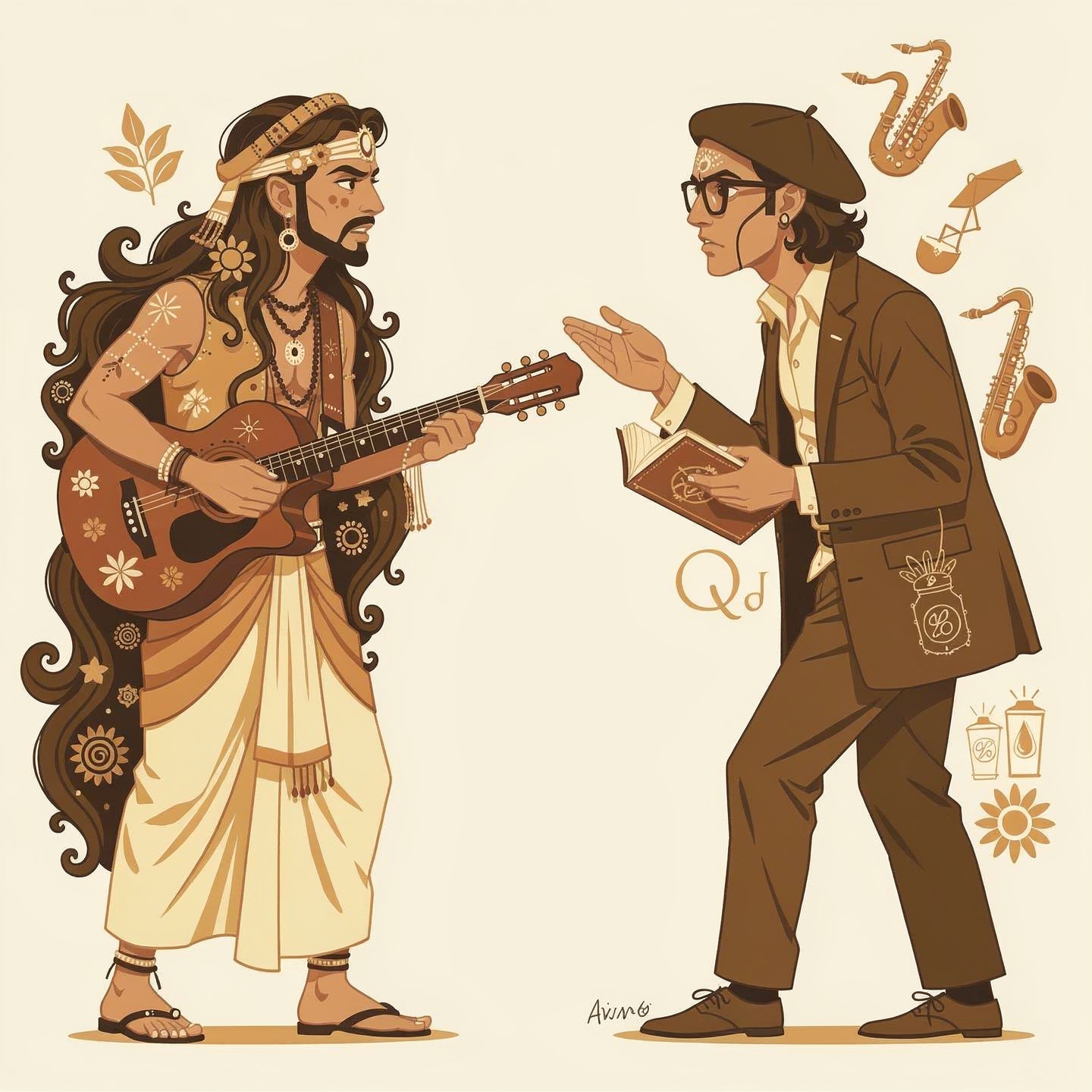

Neither of them realized the argument wasn’t really about teaching methodology. It was about hippie versus beatnik. And the divide ran deeper than either of them knew.

The Fault Line They Never Crossed

When Prabhupada arrived in America in 1965, he attracted seekers from two distinct countercultural streams. The division between them would shape ISKCON for the next fifty years.

The Beats emerged in the 1950s: intellectual rebels who read Kerouac and Ginsberg, listened to jazz, and valued individual authenticity over social conformity. They were philosophical seekers, existentialists, skeptical of group-think and suspicious of mass movements. They wanted truth, even if it was uncomfortable.

The Hippies came a decade later: communal idealists who believed in peace, love, and collective consciousness. They gathered in parks for be-ins, lived in communes, and trusted the group more than the individual. They were experiential seekers who valued feeling over analysis, community over isolation.

Both rejected mainstream American culture. But they rejected it for different reasons and in profoundly different ways.

When they encountered Krishna consciousness, something remarkable happened. Prabhupada’s message spoke to both groups. The Beats heard the rigorous philosophy, the intellectual challenge, the call to question everything including your own conditioning. The Hippies heard the emphasis on community, on devotional feeling, on the ecstatic experience of kirtan and prasadam.

Both streams flowed into the early ISKCON temples. And both brought their conditioning with them.

The problem wasn’t that they came to Krishna consciousness as hippies or beatniks. The problem was that they never fully left those identities behind. They just dressed them in dhoti, sari and tilak.

Fifty years later, that same fault line still runs through ISKCON. It shows up in three recurring flashpoints.

Temple authority. When decisions need to be made, the hippie-conditioned devotees instinctively reach for consensus and community input. Everyone should have a voice. We’re all devotees together. Hierarchy makes them uneasy. The beatnik-conditioned devotees gravitate toward meritocracy. They respect achievement, depth of study, demonstrated competence. They’re skeptical of letting popularity determine truth.

Textual interpretation. The hippie approach says the essence is love. Focus on the bhava, the feeling, the devotional emotion. Don’t get lost in dry philosophy. The beatnik approach says precision matters. Words have meanings. Intellectual honesty requires we deal with what the text actually says, not what we wish it said.

Reform movements. When both groups recognized ISKCON’s institutional problems, they organized for change, but along completely different lines. Hippie-conditioned reformers want more inclusive, democratic, emotionally-safe communities. Beatnik-conditioned reformers want intellectual integrity, textual fidelity, authentic discipleship free from institutional manipulation.

The divide persists because cultural formation runs deep. The identity you develop between fifteen and twenty-five shapes how you see the world for the rest of your life. These devotees joined ISKCON in their twenties, bringing that formation with them. Now they’re in their seventies, still operating from the same scripts.

Both groups found partial validation in Prabhupada’s teachings. He emphasized community and devotional feeling. He also emphasized rigorous philosophy and intellectual honesty. Each group heard what confirmed their existing conditioning. Each ignored (or downplayed) what challenged it.

When ISKCON’s institutional crisis erupted (the guru scandals, the financial corruption, the textual changes), each group’s conditioning determined their response. The hippies experienced it as betrayal of the community dream, the family shattered. The beatniks felt vindicated in their skepticism, their insistence that something was intellectually dishonest.

The split that was always there became a chasm.

What the Tradition Actually Teaches

The Bhagavad-gita addresses this directly. Chapter 3, verse 5 states: “Everyone is forced to act helplessly according to the qualities he has acquired from the modes of material nature; therefore no one can refrain from doing something, not even for a moment.”

Read that carefully. As long as you remain conditioned by material nature, you will be forced to act according to those qualities. This applies to everyone who hasn’t transcended their conditioning. Not just materialists. Not just people outside the temple. Devotees who’ve been chanting for fifty years, if they haven’t examined and transcended their cultural conditioning, are still being pushed by those same modes.

The hippie devotee’s instinct toward community consensus, emotional expression, and collective decision-making? Material conditioning. Mode of goodness perhaps, but still material nature.

The beatnik devotee’s drive for individual authenticity, intellectual rigor, and skepticism of group authority? Also material conditioning. Also a product of the modes.

Both groups mistake their cultural preferences for spiritual principles. The hippie thinks devotion means community feeling. The beatnik thinks advancement means philosophical precision. Both are half right. Both are half wrong.

The actual Vaishnava synthesis requires what neither group wants to hear: Community AND individual responsibility. Feeling AND philosophy. Tradition AND authentic realization.

Prabhupada saw this clearly. He warned against sentimentalism, the hippie trap. Emotional displays without philosophical grounding. All bhava, no tattva. Just feeling without understanding what you’re supposed to be feeling or why.

He also warned against dry speculation, the beatnik trap. Mental gymnastics without devotional engagement. All jnana, no bhakti. Philosophy becomes an intellectual exercise disconnected from the heart’s transformation.

Both miss the mark.

Prabhupada challenged the hippies to study philosophy seriously, not just “feel the love.” Read the books. Understand the siddhanta. Devotion without knowledge is sentiment. The hippies nodded and went back to kirtan.

He challenged the intellectuals to engage devotionally, not just analyze. Chant with feeling. Serve with love. Knowledge without devotion is speculation. The beatniks nodded and went back to their books.

Each group heard what confirmed their existing conditioning. Each filtered out what challenged it. The hippie remembered Prabhupada’s warmth and dismissed his insistence on philosophical rigor as something for “the intellectual types.” The beatnik remembered Prabhupada’s precision and dismissed his devotional demonstrations as something for “the emotional types.”

Neither recognized they were doing exactly what Bhagavad-gita 3.5 describes: acting helplessly according to their material conditioning, convinced their particular mode was spiritual advancement.

The Cost and the Way Out

The damage cascades at every level.

Personally, you have lifelong devotees (sincere, dedicated people) still operating from cultural scripts formed in the 1950s and 60s. Their spiritual practice has calcified into cultural preference. The hippie devotee’s resistance to hierarchy isn’t humility; it’s counterculture conditioning. The beatnik devotee’s intellectual independence isn’t discrimination; it’s the same conditioning, just from a different decade. Both think they’re being faithful. Both are being conditioned.

Institutionally, reform movements fracture along these exact lines. When ISKCON needed united opposition to corruption and textual manipulation, the reformers couldn’t organize together. They wanted different things. The hippies wanted healing and inclusion. The beatniks wanted accountability and precision. Both were necessary. Neither could work with the other. The institution they were trying to reform recognized the split and exploited it.

The problem runs deeper. Many of ISKCON’s gurus and sannyasis came from these same streams. They carry the same unexamined conditioning, and they naturally attract disciples who share their cultural preferences. The hippie guru emphasizes community, emotion, and collective experience. His followers feel validated in their resistance to intellectual rigor. The beatnik guru stresses philosophical precision and individual authenticity. His followers feel vindicated in their skepticism of devotional sentiment. Instead of challenging their disciples’ conditioning, these teachers reinforce it. The division perpetuates itself across generations.

Culturally, ISKCON remains trapped in 1970s America. The movement can’t attract people outside these paradigms because it’s still arguing the hippie-versus-beatnik debates of fifty years ago. Walk into most temples and you see aging devotees, veterans of a cultural moment that ended before most of today’s seekers were born. The conflicts the younger generation inherits make no sense to them. Why are these old devotees always fighting about things that seem beside the point?

Real issues (the unauthorized textual changes, the financial irregularities, the guru corruption) get filtered through hippie and beatnik lenses instead of being addressed on their own terms. The hippie sees institutional problems as failures of community and compassion. The beatnik sees them as vindication of skepticism toward authority. Both responses contain truth. Neither is complete. The movement remains stuck.

There’s a useful metaphor here. The hippie and beatnik identities were vehicles. They brought people to the shore of Krishna consciousness. But at some point, you have to leave the vehicle behind and actually cross the ocean. The vehicle got you to spiritual practice, but it can’t take you to realization.

Most didn’t. They just parked at the shore and repainted the vehicle in ISKCON colors.

For individuals, this means several concrete steps. Identify which stream you came from. Notice when your preferences align suspiciously perfectly with cultural scripts from sixty years ago. When that happens, get curious. Is this actually what the tradition teaches, or is this what makes you comfortable? Study the aspects of Krishna consciousness that challenge your conditioning, not just the parts that confirm it. Build relationships with devotees from the other stream. Let them show you what you’re missing.

For communities, it means naming this dynamic without condemnation. These were sincere seekers who found something real. But they brought something with them that they never fully examined. Stop letting cultural preferences masquerade as philosophical positions. Honor what each stream contributed (the hippies’ heart, the beatniks’ mind) while recognizing both need to be transcended.

This is conditioning, not destiny. What was learned can be unlearned. The tradition itself offers the tools. Bhagavad-gita 3.5 diagnoses the disease. The rest of the Gita provides the cure. But you have to be willing to take the medicine, even when it tastes like a challenge to everything you’ve assumed about yourself for the last fifty years.

The question is whether we’re willing to actually do that.