When A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada’s Bhagavad-gita As It Is was first published in 1972, it represented his complete vision for presenting this ancient Sanskrit text to Western audiences. After his passing in 1977, the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (BBT) undertook a revision project that resulted in a substantially modified 1983 edition. The question of whether these changes improved or compromised the work has been debated for decades. This article examines the scope and nature of these changes through statistical analysis.

The Scale of Revision

A systematic comparison between the 1972 Macmillan edition and the 1983 revised edition reveals extensive modifications. Independent researchers have documented thousands of changes across the text, ranging from minor punctuation adjustments to substantial rewording of translations and purports (commentaries).

According to documented analyses, the revisions include:

- Approximately 5,000+ individual changes to the purports (Prabhupada’s commentaries)

- Modifications to nearly every chapter, with some chapters seeing changes in over 50% of verses

- Alterations to word-for-word Sanskrit translations

- Restructuring of sentence patterns and paragraph breaks

- Changes to theological terminology and philosophical explanations

The BBT has stated that these revisions were made to correct grammatical errors, improve readability, and align the text more closely with Prabhupada’s original dictations and the Sanskrit source. Critics, however, question whether all changes served these stated purposes.

Categories of Changes

The modifications fall into several distinct categories:

1. Grammatical and Stylistic Improvements

Many changes involve correcting obvious grammatical errors or improving sentence flow. For example, articles (a, an, the) were added where missing, and awkward phrasings were smoothed out. These changes generally maintain the original meaning while enhancing readability.

2. Doctrinal Clarifications

Some revisions appear intended to clarify or modify theological positions. In several instances, terms like “impersonal” were changed to “impersonalist,” potentially shifting the emphasis of critiques against certain philosophical schools. Other changes modified descriptions of the relationship between the soul and God, or explanations of specific yogic practices.

3. Additions and Deletions

Certain purports saw substantial additions of new material or removal of existing content. In some cases, entire sentences or paragraphs were added to expand on concepts. In others, material present in the original was removed without explanation.

4. Translation Modifications

Even the verse translations themselves—the core sacred text—were not immune to changes. While many were minor, some involved substituting key philosophical terms or restructuring the translation in ways that altered emphasis.

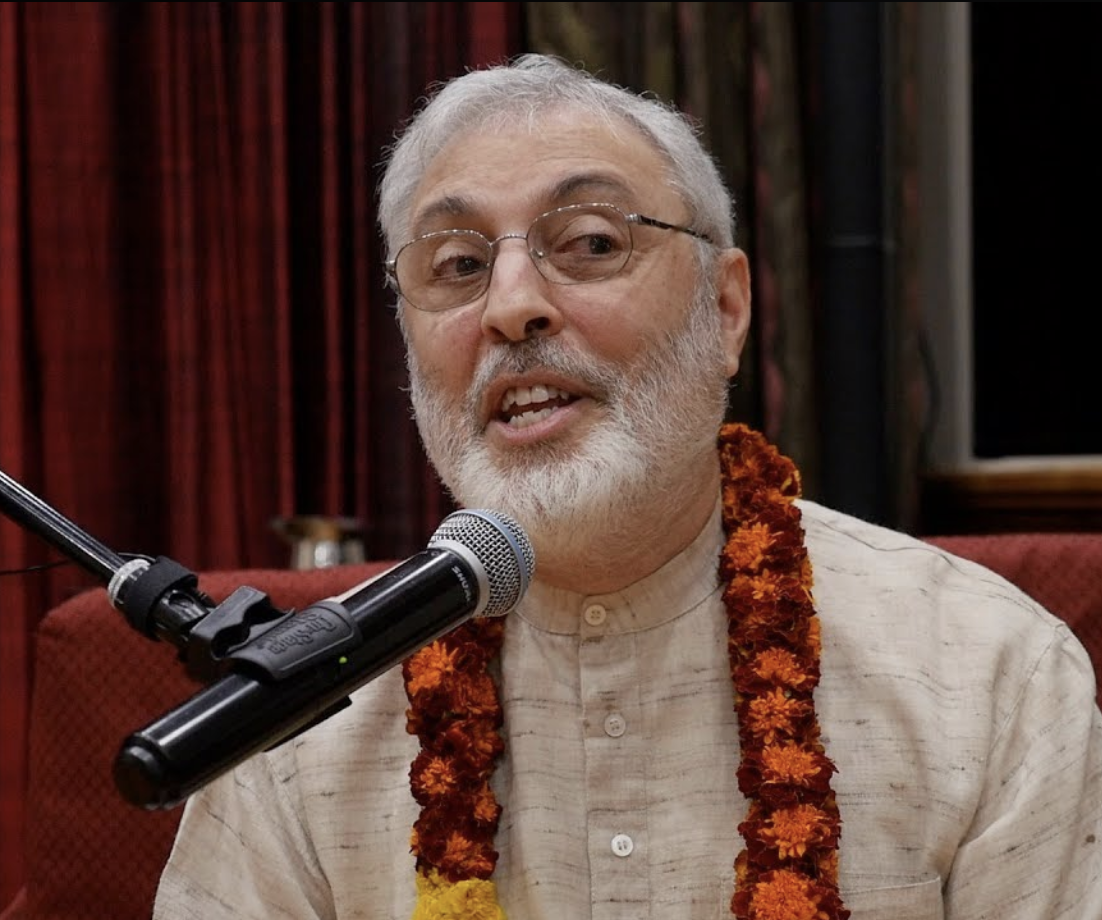

The Authorization Question

A central point of contention revolves around authorization. Prabhupada personally oversaw the 1972 edition, making corrections to galleys and expressing satisfaction with the final product. He did indicate in later years that further refinement might be beneficial, but he did not complete or explicitly authorize the specific changes that appeared in the 1983 edition.

The BBT’s position is that they worked from Prabhupada’s original dictation tapes and consulted his manuscripts to create a version more faithful to his intentions. They argue that the 1972 edition contained errors introduced during transcription and editing, which they sought to correct.

Skeptics note that Prabhupada had opportunities to revise the 1972 edition during the five years before his death but chose not to undertake such a project. They question why he would approve an imperfect edition for five years if he intended substantial revisions. Additionally, some argue that editorial judgments made after his passing, however well-intentioned, lack the authority of the author’s own choices.

Comparing Specific Examples

To understand the nature of changes, examining specific examples proves instructive:

Original (1972): “The Supersoul is the original source of all senses.”

Revised (1983): “The Supreme Lord situated in everyone’s heart is the director of the senses.”

This change expands and interprets the original statement, adding theological context that was previously implicit. Whether this constitutes clarification or interpretation depends on one’s perspective.

Another example involves changes to descriptions of devotional practice, where the revised edition sometimes employs more technical Sanskrit terminology rather than simpler English equivalents used in the original.

Statistical Patterns

Analysis of change distribution reveals interesting patterns:

- Earlier chapters saw proportionally fewer changes than later chapters

- Chapters dealing with karma-yoga and bhakti-yoga saw more extensive revisions than chapters on knowledge

- Purports criticizing impersonalism saw particularly heavy editing

- Sanskrit word-for-word translations were modified in approximately 15-20% of verses

The Broader Context

This debate occurs within a larger context of textual transmission and religious authority. Sacred texts throughout history have faced similar questions: How should texts be preserved when the original author is no longer available? Who has authority to modify, correct, or interpret? Should the emphasis be on textual preservation or on perceived improvement?

In Vedic tradition, precise textual transmission has historically been paramount, with elaborate systems developed to preserve texts exactly as received. However, translation necessarily involves interpretation, and Sanskrit texts traditionally exist in manuscript traditions that include variations.

What the Numbers Cannot Tell Us

While statistics reveal the extent of changes, they cannot definitively answer whether the revisions improved or compromised the work. A thousand minor corrections that fix genuine errors may be less significant than a single change that alters a key philosophical point. Conversely, numerous changes that enhance clarity without distorting meaning might constitute legitimate editorial work.

The question ultimately extends beyond mere quantification. It involves assessments of:

- The nature of textual authority in religious literature

- The role of editors in preserving versus interpreting an author’s work

- The balance between readability and faithfulness to original expression

- The appropriate response when apparent errors or ambiguities exist in a sacred text

Ongoing Implications

The existence of two substantially different editions has practical consequences for ISKCON devotees and scholars of the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition. Students reading different editions may encounter different phrasings of key concepts. Citations in secondary literature may refer to passages that differ between editions.

Some devotees prefer the 1972 edition precisely because Prabhupada personally approved it. Others find the 1983 edition more readable and trust the BBT’s editorial work. The debate has occasionally taken on partisan tones, though many practitioners simply remain unaware that substantial differences exist.

Conclusion

The statistical evidence confirms that the revisions to Bhagavad-gita As It Is were extensive, touching thousands of passages across the text. The data itself is not in dispute; what remains contested is interpretation. Were these changes necessary corrections of a flawed first edition, or unauthorized alterations to a completed work? The answer may depend less on counting changes and more on assessing their nature, authorization, and effect.

What the numbers do reveal is that readers of different editions are engaging with meaningfully different texts. For those who value Prabhupada’s Bhagavad-gita As It Is as a sacred work, understanding the scope of these differences—and forming one’s own view about their legitimacy—represents an important part of informed spiritual practice.

The debate ultimately raises fundamental questions about textual authority, editorial responsibility, and the transmission of spiritual teachings. These questions extend far beyond one book or one tradition, touching on challenges that any textual tradition must navigate when preserving the works of a revered teacher.